Estimation

One of the most critical skills that developers should build is breaking down a problem and predicting how long implementing a solution will take or how much it will cost. These predictions are usually called "estimates" and are a fundamental piece to any project's success.

The first step to improve your ability to estimate software is to understand the context in which an estimate is required. Think about three different concepts that are used interchangeably, but mean different things:

- A target represents a goal that's fixed and out of our control. It is a desirable objective, traditionally expressed in terms of scope, time, and budget.

- A commitment represents a promise to deliver a specific scope, on a particular date, under a predefined budget.

- An estimate is a tentative evaluation or a rough idea about how much scope we think we should deliver, by a specific date, on a budget.

Mixing these concepts can cause significant misunderstandings. As a developer, understanding which of the three is relevant in each context is key to ensuring everyone has the same expectations.

Ensure everyone is speaking the same language

An inevitable characteristic of an estimate is its inherent level of uncertainty. Communicating this and ensuring everyone interprets it the same way is challenging and a significant opportunity for miscommunication.

Here are some ways you can ensure that estimates are properly interpreted:

- If somebody gives you an estimate, ask whether it's a target or just a prediction.

- If somebody asks you for an estimate, first determine whether they are expecting a commitment.

- When providing an estimate, avoid presenting a single point number. Instead, give estimates as a range. For example, instead of saying "5 days", say "between 4 and 6 days." a. When using ranges for your estimates, use the amplitude of the range to represent uncertainty. For example, "between 4 and 6 days" is much more certain than "between 2 and 6 days".

The Cone of Uncertainty

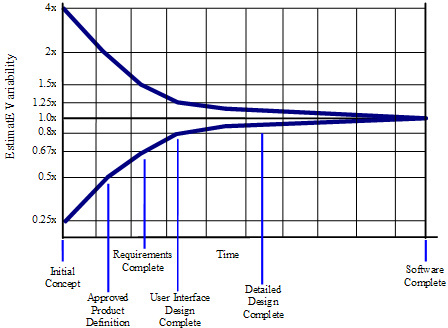

All software projects go through multiple stages from their inception through completion. When starting a project, we have most of the decisions related to tackling new functionality in front of us, so the uncertainty related to how we are going to address them is substantial. As the project moves along and we put those decisions behind us, our estimates' accuracy will increase.

The Cone of Uncertainty is an interesting way to represent how our estimates' accuracy changes as we progress through the different stages of a project.

|

|---|

| Credit: https://www.construx.com/books/the-cone-of-uncertainty |

Keep in mind that the Cone of Uncertainty shows the best possible accuracy that you can achieve at any project stage. For example, by the time you complete gathering your system's requirements, the range of uncertainty should go from 0.67x to 1.5x the estimated time or budget. Let's say you are thinking of around 12 weeks to complete the project, using the Cone of Uncertainty; you should be prepared to communicate a timeline between 8 and 18 weeks.

The Cone of Uncertainty gives you the best possible case to complete your project. Keep in mind that you can still do much worse than that, depending on how the project is managed.

Estimation Techniques

There are different estimation techniques that you can use in different circumstances. Knowing these and understanding when to apply them is a great way to reduce estimation errors.

Regardless of how you approach your estimates, keep in mind that the person/team responsible for handling a task will have the most insight into the necessary work. Try to actively participate in any estimation sessions for tasks that will eventually land on your plate.

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to have individual team members contribute to the project's estimate. In cases like this, you'll be given an estimate that you didn't create, so you'll need to adapt your approach to meet any commitments or deadlines attached to the estimate.

Let's review some of the most popular techniques to estimate a project.

Decomposition and recomposition

This technique consists of decomposing a project or task into smaller pieces, estimating each one separately, and then recomposing the individual estimate into an aggregate estimate.

Thinking about each task's granularity before estimating it is a great way to reduce the estimation error inherent in trying to tackle functionality that we don't understand.

Aim to break large tasks to a level that you can easily understand. It's hard to think about abstract features without skipping many essential details that will introduce additional work. On the other hand, be careful not to go overboard with too many low-level details that will obscure the purpose of the feature and leave you no room to operate.

Estimation by analogy

When you take a problem, break it down, and come up with an estimate based on the similarities with a previous problem you solved, you estimate by analogy.

Estimating by analogy requires experience. The more projects in your resume, the easier it will be to find similarities that will aid in coming up with a solid estimate for any new challenge.

Estimating by analogy can also introduce a lot of errors. To achieve good results, you should use accurate information about past projects. It's usually not enough to rely on a vague memory of how difficult something was, but instead, you need specifics on how long each task was and how many people were needed.

You should also make sure you break the project or tasks into smaller units that you can use to compare with your previous experience. Don't just come up with an estimate between two projects because they are similar, but instead, compare the individual pieces and build up the new estimate as a percentage of the old project.

Story Points

If you work for a company that uses agile methodologies to run their projects, you are most likely familiar with Story Points.

Estimating using Story Points is classified as part of the "Proxy-Based Estimation" technique. In this case, the concept of a Story Point (or Ideal Hours or Days on other methodologies) is a proxy correlated to the time, which is the actual variable you want to estimate.

Once you've found your proxy (in this case, the number of Story Points), you can quickly develop a time estimate for your project.

A widespread practice is to use the Fibonacci Sequence to measure tasks in Story Points. For example, each task or "story" (as described by agile methodologies) would be given one of the following estimates: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc. Notice how this differs from assigning plain hours to tasks. The larger the stories get, the more variability exists between one estimate and the next value in the sequence. This helps represent the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty of larger tasks.

Another standard practice used in agile methodologies is estimating using T-shirt sizes as a reference. When coming up with an estimate for large pieces of functionality, this is useful when breaking the work into smaller units is not practical nor undesirable. In this case, you would classify each feature into SMALL, MEDIUM, LARGE, or X-LARGE buckets.

After having an estimate using the proxy metric, the final piece is to translate it into the desired time unit, for example, hours or days. This is done through the concept of "velocity;" representing how many story points the team can complete in a sprint.

For example, if the team can complete between 40 and 50 story points every two weeks, a 300-story point project should take approximately 12 to 15 weeks (300/502 to 300/402).